Key Takeaways

- Hepatitis B spreads through contact with infected blood or bodily fluids.

- Early testing and awareness of symptoms support effective treatment.

- Vaccination and safe practices greatly reduce your risk of infection.

Hepatitis B affects your liver and can quietly progress without obvious signs until serious damage occurs. It spreads through contact with infected blood or bodily fluids, often during childbirth, unprotected sex, or sharing personal items like razors or needles. You can protect yourself and others by understanding how hepatitis B spreads, recognizing its symptoms early, and seeking timely medical care.

You might not notice symptoms right away, but fatigue, loss of appetite, nausea, and yellowing of the skin or eyes may appear as the infection develops. A simple blood test can confirm if you have the virus. With proper treatment and monitoring, most people manage the condition effectively and prevent long-term liver damage.

Contents

- Overview of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

- Difference Between Acute and Chronic Hepatitis B

- Role of the Liver in Hepatitis B

- Blood-to-Blood Contact and Transmission

- Sexual Transmission and Unprotected Sex

- Mother-to-Child Transmission

- Sharing Needles and Personal Items

3. Symptoms and Early Warning Signs

- Common Symptoms of Hepatitis B

- Recognizing Acute Versus Chronic Symptoms

- Complications and Severe Manifestations

Vaccination Program

Explore our range of vaccination programs designed for your specific health needs.What Is Hepatitis B?

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that causes inflammation of your liver and can lead to both short- and long-term illness. Understanding how the hepatitis B virus (HBV) affects your body helps you recognize the importance of early testing, vaccination, and ongoing monitoring of liver health.

Overview of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV)

Hepatitis B results from infection with the hepatitis B virus (HBV), a DNA virus that targets the liver. The virus spreads through contact with infected blood, semen, or other body fluids. Common transmission routes include unprotected sex, sharing needles, and from mother to child during childbirth.

HBV can survive outside the body for several days, which makes it easier to spread than some other viruses. You cannot get hepatitis B from casual contact such as hugging, sharing food, or coughing.

Once HBV enters your bloodstream, it travels to the liver, where it multiplies inside liver cells. Your immune system’s response to this infection causes liver inflammation, which can range from mild irritation to more serious damage. Vaccination provides strong protection by triggering your immune system to recognize and fight off HBV before it causes harm.

Difference Between Acute and Chronic Hepatitis B

Acute hepatitis B occurs within the first six months after exposure. Many people recover fully without lasting effects. Some experience symptoms such as fatigue, nausea, dark urine, or yellowing of the skin and eyes. Others may have no symptoms but can still spread the virus.

If your body clears the virus naturally, you develop immunity. However, if HBV remains in your system for more than six months, it becomes chronic hepatitis B. Chronic infection can last a lifetime and may gradually damage your liver.

Over time, chronic hepatitis B increases your risk of cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. Regular medical monitoring, antiviral medication, and healthy lifestyle habits help slow disease progression and protect your liver.

| Type: Acute | |

|---|---|

| Duration | < 6 months |

| Possible Outcome | Full recovery or progression |

| Key Concern | Transmission to others |

| Type: Chronic | |

|---|---|

| Duration | > 6 months |

| Possible Outcome | Ongoing infection |

| Key Concern | Long-term liver damage |

Role of the Liver in Hepatitis B

Your liver performs vital functions, including filtering toxins, storing nutrients, and producing bile for digestion. When HBV infects liver cells, your immune system attacks these infected cells, leading to liver inflammation.

This inflammation can cause scarring, known as fibrosis, and over time may progress to cirrhosis, which limits the liver’s ability to function. Chronic inflammation also raises the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma, a type of liver cancer.

Supporting your liver health is essential if you have hepatitis B. Avoid alcohol, maintain a balanced diet, and consult your healthcare provider before taking any medications or supplements that could stress your liver. Regular blood tests and imaging help track liver function and detect changes early.

How Hepatitis B Spreads

Hepatitis B spreads when blood or certain body fluids from an infected person enter your body. The virus does not spread through casual contact, contaminated food, or contaminated water. Understanding how transmission occurs helps you take steps to protect yourself and others.

Blood-to-Blood Contact and Transmission

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) spreads most efficiently through direct blood-to-blood contact. Even a small amount of infected blood can transmit the virus. You can be exposed through open cuts, medical procedures using unsterilized equipment, or contact with contaminated surfaces.

Health care workers face a higher risk due to potential needle-stick injuries. Using sterile medical equipment and following standard precautions greatly reduces this risk. Blood transfusions are now screened carefully, making transmission through donated blood extremely rare.

Accidental exposure can also occur in settings where blood is present, such as tattoo or piercing studios that do not follow proper sanitation practices. Always ensure that single-use or properly sterilized instruments are used.

Sexual Transmission and Unprotected Sex

You can contract HBV through unprotected sex with an infected partner. The virus is present in semen, vaginal fluids, and blood. Any small tear or abrasion in the skin or mucous membranes can allow the virus to enter your body.

Using condoms or dental dams during sexual activity significantly lowers the risk of transmission. HBV spreads more easily than HIV through sexual contact because it survives outside the body for longer periods.

People with multiple sexual partners or those who engage in sex without protection face a higher risk. Getting vaccinated against hepatitis B provides strong protection and is recommended for anyone who may be exposed through sexual contact.

Mother-to-Child Transmission

A mother with hepatitis B can pass the virus to her baby during childbirth. This type of perinatal transmission is one of the most common ways HBV spreads worldwide. The risk is high if the mother has a high viral load near delivery.

Newborns can be protected through immediate vaccination and an injection of hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) within 12 hours after birth. These steps are highly effective at preventing infection.

Breastfeeding is considered safe if the baby has received proper immunization. Routine screening of pregnant women for HBV helps ensure early protection for both mother and child.

Sharing Needles and Personal Items

Sharing needles, syringes, or other drug-injection equipment is a major route of HBV transmission. The virus can survive for days in dried blood, making even old or seemingly clean equipment dangerous. Using sterile, single-use supplies prevents this risk.

You can also be exposed by sharing personal items that may have traces of blood, such as razors, toothbrushes, or nail clippers. Avoid sharing these items, even within households where someone has chronic hepatitis B.

Safe disposal of needles and maintaining good hygiene practices protect you and others from accidental exposure. Vaccination remains the most reliable defense if you are at risk of contact with infected blood.

Symptoms and Early Warning Signs

Hepatitis B can affect your body in different ways depending on how long you’ve had the infection and how your immune system responds. You may notice mild, flu-like symptoms at first, but the infection can also remain silent for months or years before showing clear signs of liver involvement.

Common Symptoms of Hepatitis B

In the early stage, you might experience fatigue, loss of appetite, and nausea. These symptoms often appear gradually and can be mistaken for a mild viral illness. Some people also report vomiting, joint pain, or a general feeling of weakness.

As the liver becomes more inflamed, jaundice (yellowing of the skin and eyes) may develop. Dark urine and pale stool are other important clues that your liver is not processing waste properly.

You may also feel abdominal pain, especially on the right side under your ribs where the liver sits. These symptoms can last several weeks and usually resolve as the body clears the virus, but in some cases, they persist or return.

| Symptom: Fatigue | |

|---|---|

| Description | Feeling unusually tired or weak |

| Symptom: Jaundice | |

|---|---|

| Description | Yellowing of skin and eyes |

| Symptom: Dark urine | |

|---|---|

| Description | Brown or tea-colored urine |

| Symptom: Pale stool | |

|---|---|

| Description | Light or clay-colored bowel movements |

| Symptom: Abdominal pain | |

|---|---|

| Description | Discomfort in the upper right side of the abdomen |

Recognizing Acute Versus Chronic Symptoms

Acute hepatitis B occurs soon after infection and may last up to six months. During this phase, you might have fever, nausea and vomiting, and loss of appetite, followed by jaundice. Many people recover fully, and the virus clears naturally.

If the infection persists beyond six months, it becomes chronic hepatitis B. Chronic infection often causes no immediate symptoms, which makes it harder to detect. Over time, you may notice ongoing fatigue, mild abdominal pain, or joint discomfort.

Because chronic hepatitis B can silently damage your liver, regular blood tests and medical follow-up are essential to monitor liver function and detect complications early.

Complications and Severe Manifestations

When hepatitis B progresses without treatment, it can lead to serious liver problems. Persistent inflammation may cause fibrosis (scarring) and eventually cirrhosis, which affects how your liver filters toxins and produces essential proteins.

You may experience swelling in the abdomen, easy bruising, or persistent jaundice as liver function declines. In some cases, acute liver failure can occur, though this is rare.

Long-term infection also increases the risk of liver cancer. Early detection and consistent medical care can greatly reduce these risks and help protect your liver health over time.

Diagnosing Hepatitis B

Accurate diagnosis of hepatitis B depends on evaluating how well your liver functions, identifying viral markers in your blood, and assessing the liver’s structure and damage level. These steps help determine whether the infection is acute or chronic and guide the most effective treatment plan.

Liver Function Tests and Enzyme Markers

Your healthcare provider checks liver function tests (LFTs) to measure how well your liver works. These tests focus on enzymes such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST), which rise when liver cells are damaged.

| Test: ALT | |

|---|---|

| Normal Range (approx.) | 7–56 U/L |

| What It Indicates | Elevated levels suggest liver inflammation or injury |

| Test: AST | |

|---|---|

| Normal Range (approx.) | 10–40 U/L |

| What It Indicates | High values may indicate liver or muscle damage |

| Test: Bilirubin | |

|---|---|

| Normal Range (approx.) | 0.1–1.2 mg/dL |

| What It Indicates | Increased levels can cause jaundice |

| Test: Albumin | |

|---|---|

| Normal Range (approx.) | 3.5–5.0 g/dL |

| What It Indicates | Low levels suggest impaired liver synthesis |

You may also have tests for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) to assess bile duct involvement. Persistent enzyme elevations often signal chronic hepatitis or ongoing liver injury.

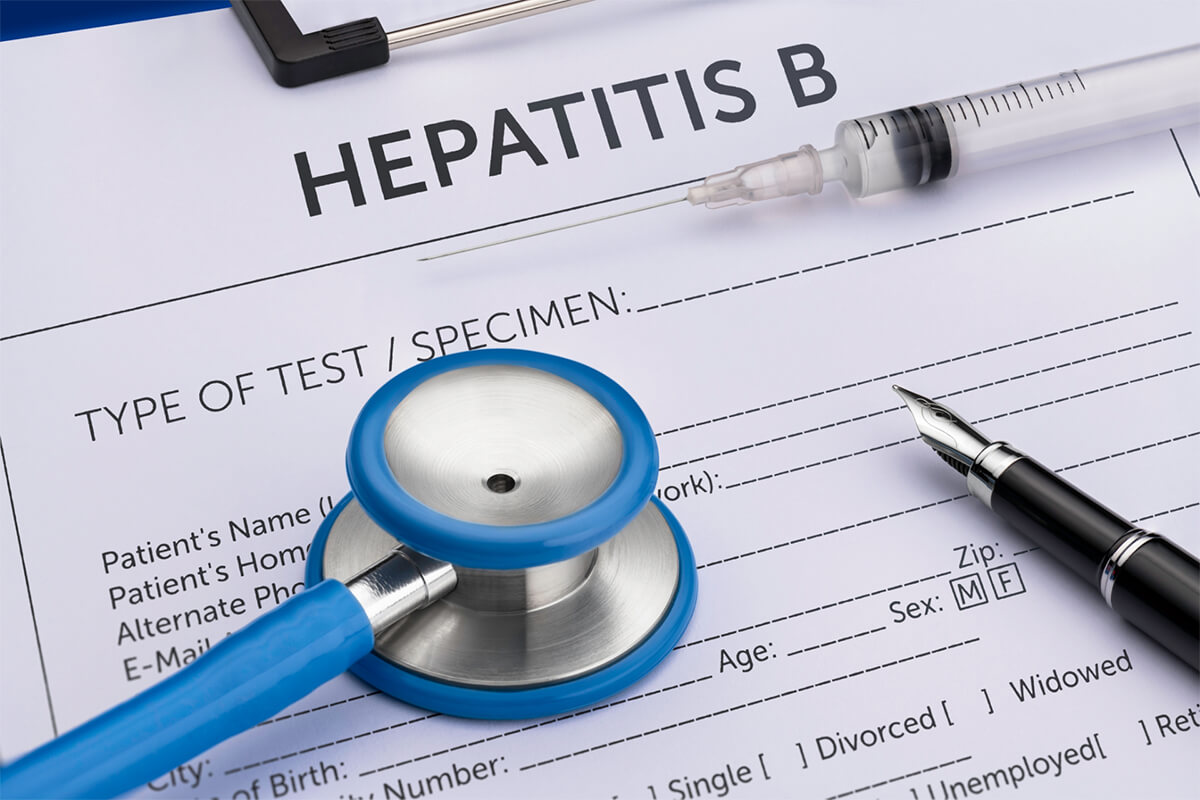

Blood Tests for Hepatitis B

Blood tests confirm whether you have hepatitis B and identify the stage of infection. The main markers include hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs), and hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc).

- HBsAg indicates current infection.

- Anti-HBs shows immunity from vaccination or recovery.

- Anti-HBc (IgM or total) helps distinguish recent from past infection.

Quantitative HBV DNA testing measures the amount of virus in your blood, helping monitor treatment response. In some cases, additional markers such as HBeAg and anti-HBe are used to evaluate viral replication and infectivity. These tests are essential for determining whether antiviral therapy is needed.

Imaging and Liver Biopsy

If blood tests suggest liver damage, imaging studies such as ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI help visualize liver size, structure, and possible fibrosis. These noninvasive methods detect cirrhosis, fatty changes, or tumors that may develop from chronic infection.

When imaging results are unclear or detailed evaluation is required, your doctor may recommend a liver biopsy. During this procedure, a small tissue sample is taken and examined under a microscope. A biopsy provides direct information on inflammation, scarring, and the stage of liver disease.

In some cases, transient elastography (FibroScan) is used instead to measure liver stiffness without needles, offering a safer alternative for many patients.

Treatment and Management Options

Effective treatment for hepatitis B focuses on controlling the virus, protecting your liver from further damage, and reducing the risk of complications such as cirrhosis and liver cancer. Care often involves long-term medication, routine monitoring, and lifestyle adjustments to support liver health.

Antiviral Medications

Antiviral medications help slow down or stop the hepatitis B virus from multiplying in your body. The most common options include tenofovir and entecavir, both taken as daily oral tablets. These drugs are highly effective and have a low risk of resistance when used correctly.

Your doctor may recommend treatment if blood tests show high viral levels or signs of liver inflammation. Antivirals rarely cure hepatitis B completely, but they can suppress the virus to undetectable levels.

In some cases, treatment continues for years or even for life. Regular follow-up testing helps ensure the medication remains effective and that your liver stays stable. Stopping treatment without medical advice can cause the virus to rebound and worsen liver injury.

| Antiviral: Tenofovir | |

|---|---|

| Typical Use | First-line therapy |

| Key Benefit | Strong viral suppression |

| Antiviral: Entecavir | |

|---|---|

| Typical Use | First-line therapy |

| Key Benefit | Low resistance risk |

Managing Chronic Hepatitis B

If you have chronic hepatitis B, your goal is to prevent liver damage and maintain normal liver function. This involves consistent medical care, healthy habits, and avoiding substances that strain the liver.

You should avoid heavy alcohol use and limit medications or supplements that can harm the liver. Eating a balanced diet and maintaining a healthy weight can also reduce stress on your liver.

Your healthcare provider may schedule periodic blood tests to check viral load, liver enzyme levels, and immune activity. If your immune system controls the virus naturally, you may not need medication right away, but ongoing observation remains essential.

Vaccination of household members and safe practices to prevent transmission protect others from infection.

Monitoring for Liver Damage and Cancer

Chronic hepatitis B increases your risk of cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma (a type of liver cancer). Regular monitoring helps detect these complications early, when treatment is most effective.

Doctors usually recommend ultrasound imaging and blood tests for alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) every six months. These tests help identify early signs of liver cancer or scarring.

If advanced liver disease develops, you may need additional interventions such as antiviral therapy adjustments or evaluation for a liver transplant.

Close coordination with a liver specialist ensures that any changes in your condition are addressed quickly, helping you maintain the best possible long-term health.

Prevention and Reducing Risk

You can lower your risk of hepatitis B through vaccination, safe lifestyle choices, and quick action after possible exposure. Protective measures also help prevent other liver infections such as hepatitis A, C, D, and E, which share some transmission routes.

Hepatitis B Vaccine

The hepatitis B vaccine is the most effective way to prevent infection. It triggers your immune system to produce antibodies that protect you from the virus. The standard schedule includes three doses over six months, though combination vaccines may include protection against hepatitis A (HAV).

Infants usually receive the first dose at birth. Adults who have not been vaccinated—especially healthcare workers, people with multiple sexual partners, or those who inject drugs—should complete the full series.

If you have a weakened immune system or chronic liver disease such as autoimmune hepatitis or alcoholic hepatitis, vaccination becomes even more important. The vaccine does not treat existing infection but prevents future exposure from causing illness.

Keeping your vaccination record updated ensures long-term immunity and reduces the spread of hepatitis B and related viruses like HDV, which require hepatitis B to replicate.

Safe Practices and Lifestyle Choices

You can reduce risk by avoiding direct contact with infected blood or bodily fluids. Use condoms during sexual activity, and never share razors, toothbrushes, or needles. If you get tattoos or piercings, confirm that equipment is properly sterilized.

Healthcare and laboratory workers should follow standard precautions, including gloves and safe needle disposal. For travelers, drinking safe water and eating well-cooked food helps prevent other liver infections such as HAV and HEV.

Avoid heavy alcohol use, which can worsen liver inflammation and increase complications like ascites—fluid buildup in the abdomen. Maintaining a healthy weight and avoiding unnecessary medications that strain the liver also support long-term liver health.

What to Do If You’ve Been Exposed

If you think you’ve been exposed to hepatitis B, act quickly. Within 24 hours, seek medical care for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), which may include the hepatitis B vaccine and hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG).

Doctors assess your vaccination history and exposure type before deciding on treatment. Early intervention can prevent infection from developing.

Avoid donating blood or engaging in unprotected sex until your doctor confirms you are not infected. If you already have hepatitis B or another liver condition like Wilson’s disease, follow your care plan closely to protect your liver and prevent additional complications.