Key Takeaways

- CAP is a lung infection that develops outside of hospitals.

- It often causes fever, cough, and breathing difficulty.

- Early care and preventive steps reduce complications.

When you come down with a cough and fever that just won’t go away, you might be dealing with more than a simple cold. Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a lung infection you catch outside of a hospital, caused by bacteria, viruses, or other germs that inflame the air sacs in your lungs and make it hard to breathe. It can range from mild to serious, but understanding it early helps you act fast and recover better.

You can get CAP anywhere—at home, work, or school—especially when your immune system is tired or you have another health condition. Symptoms often start with fever, chills, shortness of breath, and chest discomfort. Knowing what’s normal and what’s not makes it easier to spot when you need medical care.

Treatment usually involves antibiotics or antivirals, rest, and plenty of fluids. Vaccines and good hygiene go a long way in preventing it. Learning how CAP happens and how to manage it helps you protect yourself and those around you.

What Is Community-Acquired Pneumonia?

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a lung infection that develops when you are living your normal daily life, not while staying in a hospital or long-term care facility. It affects your ability to breathe comfortably and can range from mild illness to a serious condition requiring hospitalization.

How CAP Differs From Other Types of Pneumonia

You get community-acquired pneumonia outside of hospitals or healthcare settings. In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) occur in people already receiving medical care.

The cause and treatment can differ because the germs found in hospitals often resist common antibiotics.

CAP usually results from bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae or Haemophilus influenzae. Sometimes, viruses like influenza or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are responsible.

You might notice symptoms such as fever, cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath, which develop over hours or days.

Doctors diagnose CAP through a physical exam, chest imaging, and lab tests. Treatment often involves antibiotics, rest, and fluids, depending on the cause and severity.

Unlike hospital-acquired infections, CAP generally responds well to early care and preventive steps like vaccination.

Who Is Most at Risk for CAP

Anyone can get CAP, but some people are more vulnerable. Older adults, young children, and those with weakened immune systems have the highest risk. Chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, or lung disorders also make you more likely to develop serious illness.

Lifestyle and environment matter too. Smoking, poor nutrition, and exposure to air pollution can weaken your lungs’ natural defenses.

If you live in crowded spaces or work in healthcare, your exposure to respiratory germs increases.

Each year, CAP leads to millions of medical visits worldwide and remains a leading cause of hospitalization among adults. Recognizing symptoms early and seeking care can help reduce complications and recovery time.

How CAP Spreads in the Community

CAP spreads when you inhale droplets from a cough or sneeze of an infected person. These droplets can carry bacteria or viruses into your lungs.

Sometimes, you can also develop CAP when germs already in your mouth or throat move into your lungs.

You can lower your risk by practicing good hygiene, such as washing your hands, covering your mouth when coughing, and avoiding close contact with sick individuals.

Vaccines against influenza and pneumococcal bacteria protect against common causes of CAP.

Maintaining a strong immune system through balanced nutrition, adequate rest, and regular medical checkups further reduces your chances of infection.

These small steps can make a big difference in keeping your lungs healthy and preventing serious illness.

Causes and Risk Factors

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) happens when germs infect your lungs outside a hospital or care setting. The infection can come from bacteria, viruses, or less common organisms that affect how your lungs exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide. Your health, habits, and environment all play a role in how likely you are to get it.

Common Bacterial Causes of CAP

Bacteria cause most cases of CAP. The most frequent is Streptococcus pneumoniae, often called pneumococcal pneumonia. It can lead to fever, cough, and chest pain, especially in older adults or people with chronic illnesses.

Other frequent bacteria include Haemophilus influenzae, which often affects people with COPD or smokers, and Moraxella catarrhalis, seen in those with chronic lung disease.

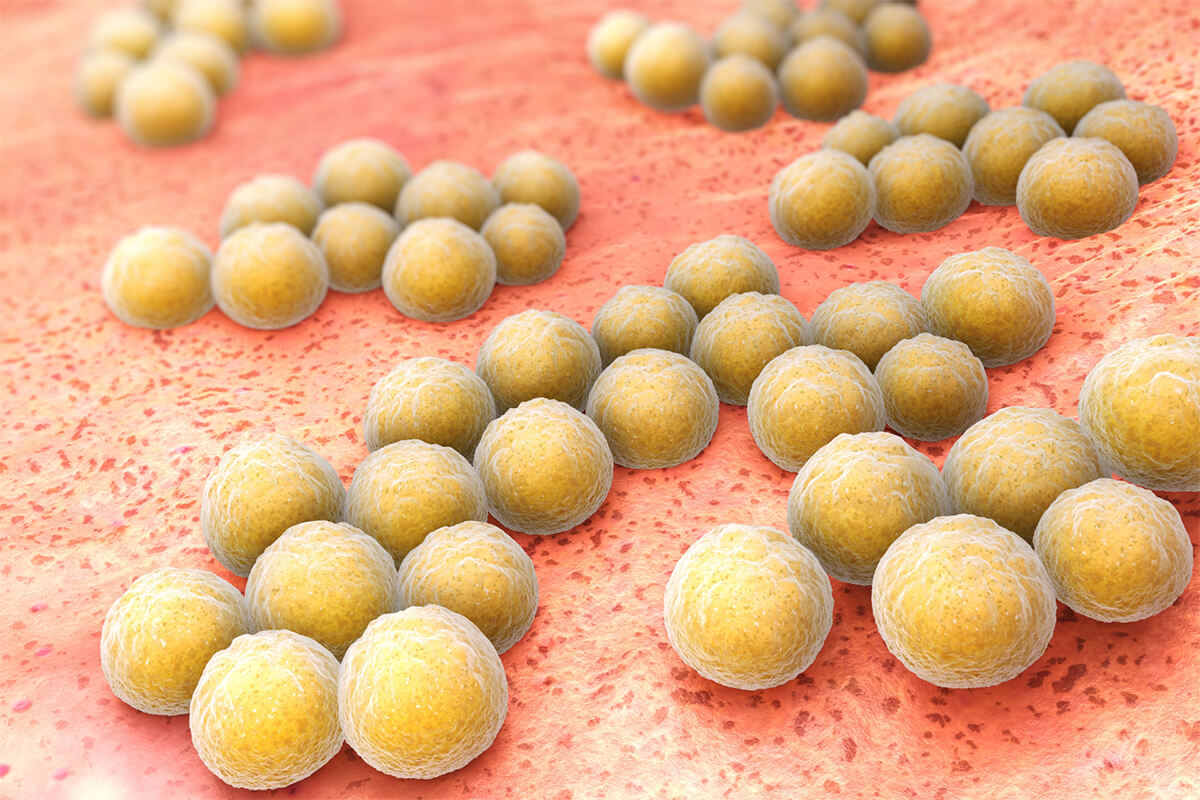

Some infections come from Staphylococcus aureus, including methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA). These can occur after the flu or in people with weakened immune systems.

Legionella pneumophila (Legionnaires’ disease) spreads through inhaling contaminated water droplets, not person-to-person contact. It can cause severe pneumonia with high fever and confusion.

| Bacteria: Streptococcus pneumoniae | |

|---|---|

| Typical Setting or Risk | Most common overall |

| Bacteria: Haemophilus influenzae | |

|---|---|

| Typical Setting or Risk | COPD, smoking |

| Bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus | |

|---|---|

| Typical Setting or Risk | Post-influenza, immune weakness |

| Bacteria: Legionella pneumophila | |

|---|---|

| Typical Setting or Risk | Contaminated water exposure |

Viral Causes and Their Impact

Viruses are a leading cause of pneumonia, especially in winter. Influenza virus and rhinovirus are common triggers. These viruses can directly cause viral pneumonia or weaken your lungs, allowing bacteria to infect more easily.

SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, can lead to severe lung inflammation and low oxygen levels. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) affects both children and older adults, sometimes leading to hospitalization.

Unlike bacterial pneumonia, viral infections often start with flu-like symptoms—fever, cough, and fatigue—before shortness of breath develops.

Vaccines for influenza and COVID-19 help lower your risk and lessen the severity if you do get infected. Good hand hygiene and avoiding close contact when sick also reduce spread.

Other Pathogens and Less Common Causes

Some cases of CAP come from less typical organisms. Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae cause “atypical” pneumonia, which usually develops slowly with a dry cough and mild fever.

Chlamydia psittaci, linked to bird exposure, causes psittacosis, a rare infection that can lead to high fever and headache. Fungal and mycobacterial infections, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, are uncommon but possible in people with weakened immune systems.

These infections often require specific tests for diagnosis because their symptoms can mimic viral or bacterial pneumonia. Recognizing unusual exposures—like birds or contaminated water—can help doctors find the cause faster.

Key Risk Factors for Developing CAP

Your risk of CAP rises if your immune system is weakened or if you have chronic conditions like diabetes, COPD, asthma, or HIV. These conditions make it harder for your body to clear germs from the lungs.

Smoking damages the airways and reduces your lungs’ natural defenses, increasing the chance of infection. Older age, poor nutrition, and alcohol misuse also make you more vulnerable.

Environmental exposures, such as crowded living spaces or poor indoor air quality, can add to your risk. Keeping up with vaccinations, managing chronic illnesses, and quitting smoking are practical steps you can take to protect your lungs.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) affects your lungs and breathing, often starting with mild symptoms that can quickly become more serious. Recognizing early warning signs and getting an accurate diagnosis helps ensure you receive the right treatment and avoid complications.

Typical Signs and Symptoms of CAP

You may first notice fever, chills, and fatigue. A cough that produces sputum (mucus) is common, though in some cases the cough may be dry. Pleuritic chest pain—sharp pain that worsens when you breathe deeply or cough—can occur as the infection irritates the lung lining.

Shortness of breath (dyspnea) often develops as the lungs fill with fluid or inflammation spreads. Some people experience rapid breathing or a fast heartbeat.

Older adults may show less obvious signs such as confusion or weakness instead of fever. Severe cases can lead to empyema (pus in the pleural space), lung abscess, sepsis, or acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), which require urgent medical care.

| Symptom: Fever and chills | |

|---|---|

| Description | Body’s immune response to infection |

| Symptom: Cough with sputum | |

|---|---|

| Description | Often yellow or green mucus |

| Symptom: Chest pain | |

|---|---|

| Description | Sharp or aching pain when breathing |

| Symptom: Dyspnea | |

|---|---|

| Description | Shortness of breath or labored breathing |

| Symptom: Fatigue | |

|---|---|

| Description | Feeling unusually tired or weak |

How Doctors Diagnose CAP

Doctors diagnose CAP by combining your symptoms, physical exam findings, and test results. They listen to your lungs for crackles, wheezes, or dullness that suggest infection.

A chest x-ray confirms the diagnosis by showing an area of lung inflammation or consolidation. Your doctor will also ask about recent illnesses, travel, or exposure to others with respiratory infections to rule out other causes.

They may consider differential diagnoses such as pulmonary embolism or cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, which can mimic CAP symptoms. Identifying the correct cause ensures you get targeted treatment and helps prevent unnecessary antibiotics.

Tests and Tools Used in Diagnosis

Several tests help confirm CAP and assess its severity. A complete blood count (CBC) checks for elevated white blood cells, which signal infection. Sputum cultures or a nasopharyngeal swab can identify the bacteria or virus responsible.

Rapid tests such as influenza testing or multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) panels detect common respiratory pathogens. Blood tests like procalcitonin levels may help distinguish bacterial from viral infections.

Doctors often use scoring tools like the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) or CURB-65 to decide if you need hospital care. These tools consider factors such as age, oxygen levels, and blood pressure to estimate risk of complications or mortality.

Treatment and Prevention

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) can often be managed effectively with timely antibiotics, supportive care, and preventive measures. The right treatment depends on the severity of your illness, your age, and any other health conditions you may have. Vaccination and healthy habits can reduce your risk of future infections.

Antibiotic Therapy and Medication Options

If your doctor suspects bacterial CAP, you’ll likely start antibiotic therapy right away. Amoxicillin, doxycycline, or a macrolide such as azithromycin are common first-line options for otherwise healthy adults treated at home. These medicines target the most frequent bacterial causes of pneumonia.

For people with chronic illnesses or more severe symptoms, combination therapy may be used. This often includes amoxicillin-clavulanate or a cephalosporin like ceftriaxone, paired with a macrolide or levofloxacin. Doctors follow clinical practice guidelines from the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America to choose the best regimen.

In hospitals, intravenous antibiotics such as cefepime or vancomycin may be needed, especially for resistant bacteria or immunocompromised patients. If a viral infection like influenza or COVID-19 is identified, antivirals such as oseltamivir may be added.

Your care team will adjust treatment based on test results and your response to therapy. Following antibiotic stewardship principles helps prevent resistance and ensures antibiotics remain effective.

When Hospitalization Is Needed

You may need hospital care if you have severe shortness of breath, low oxygen levels, confusion, or very low blood pressure. In the emergency department, doctors assess your vital signs and may order imaging and lab tests to confirm pneumonia and gauge its severity.

If your oxygen level is low, you’ll receive supplemental oxygen. Some people require a ventilator or noninvasive breathing support. Patients with severe CAP are often admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) for close monitoring.

Corticosteroids may be prescribed to reduce inflammation in severe cases. Hospital stays typically last several days, with intravenous antibiotics given until your condition stabilizes. After discharge, you may continue oral antibiotics and sometimes rehabilitation to regain strength and lung function.

Preventing CAP Through Vaccination and Healthy Habits

You can lower your risk of CAP through consistent preventive care. Vaccination plays a key role. Adults should stay current with the pneumococcal vaccine, flu shot, and COVID-19 boosters. These vaccines help prevent infections that often lead to pneumonia or reduce their severity.

Avoiding smoking and limiting alcohol use protect your lungs and immune system. Good oral hygiene—brushing your teeth twice daily and visiting your dentist regularly—also reduces bacterial buildup that can contribute to pneumonia.

If you have swallowing difficulties, eat slowly, take small bites, and remain upright for 30 minutes after meals to reduce aspiration risk. Regular exercise and managing chronic conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, or COPD further decrease your chances of developing CAP.